There is a beautiful poem ascribed to Vedānta-deśika (born Veṅkaṭanātha) that deals with the topic of vairāgya (detachment from worldly indulgences).

क्षोणी-कोण-शतांश-पालन-कला-दुर्वार-गर्वानल-

क्षुभ्यत्-क्षुद्र-नरेन्द्र-चाटु-रचना-धन्यान्-न मन्यामहे।

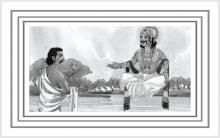

देवं सेवितुम्-एव निश्चिनुमहे योऽसौ दयालुः पुरा

धाना-मुष्टिमुचे कुचेल-मुनये दत्ते स्म वित्तेशताम्॥ 1

(Meter: Śārdūlavikrīḍitam)