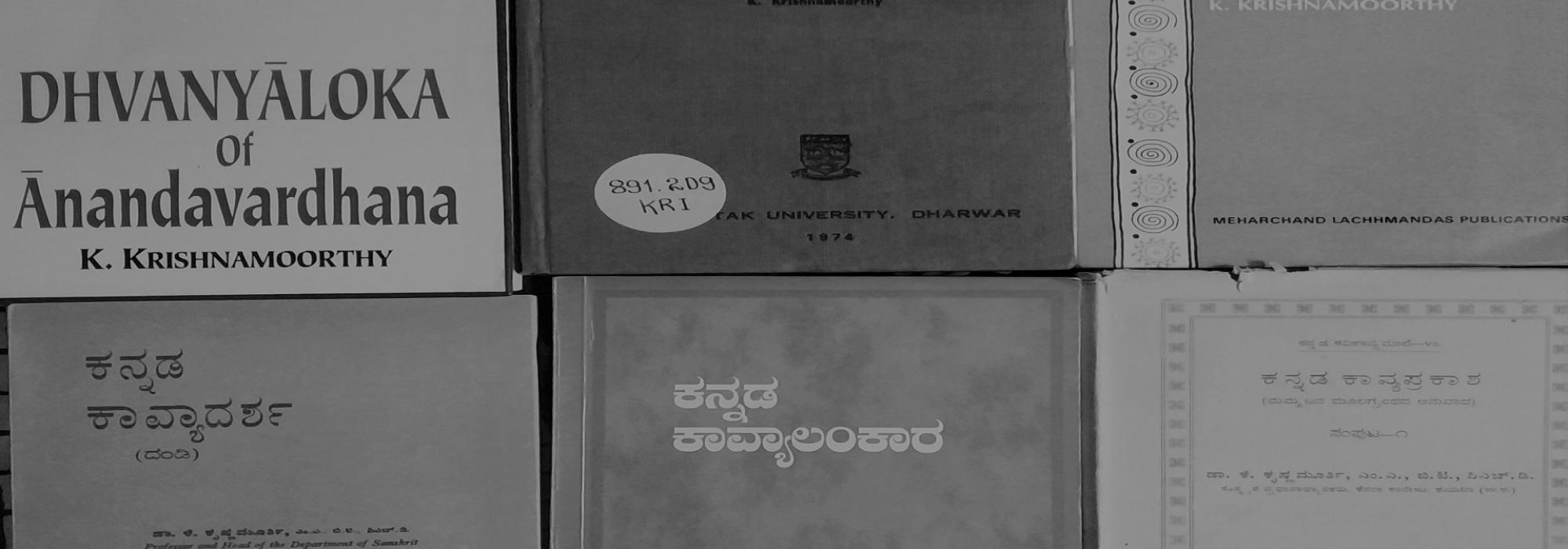

Krishnamoorthy joined the Sharada Vilas College in 1949 and worked there until 1952. During this time, at the behest of A R Krishna Shastri, he wrote an elaborate introduction to Ānandavardhana’s aesthetic method and translated Dhvanyāloka into Kannada. In the introduction, he outlined the concepts of kindred subjects that are essential to understand Dhvanyāloka, summarized the contents of the text and explained them with apt examples chosen from Kannada poems, both ancient and modern. This essay is one of the finest expositions of Ānandavardhana’s contribution to Indian aesthetics. Krishnamoorthy’s maturity in handling the subject, broad sweep in choosing illustrative examples, perfect aesthetic taste in explaining them, prose style that is at once elegant and captivating – these qualities effectively hide the fact that this essay is his first attempt at writing in Kannada! His Kannada rendering of Dhvanyāloka has set the gold standard for translation.

A R Krishna Shastri helped at every stage in the preparation and production of this monumental work. He inspired Krishnamoorthy to take it up, corrected the proofs and moved heaven and earth to ensure its publication in Prabuddha Karṇāṭaka, a journal he had founded a few decades ago. Krishnamoorthy initially wrote only on Ānandavardhana’s aesthetic method and went to Krishna Shastri to get a foreword. The latter thundered: “I asked you to write a thesis and translate the treatise into Kannada. You have written a foreword to dhvani. How can I write a foreword to a foreword!”

The background story was that the editors of the journal had requested Krishnamoorthy to write in a concise form because they had received flak from some vested interests that Prabuddha Karṇāṭaka is turning into Krishnamoorthy’s mouthpiece. When Krishna Shastri came to know this, he wasted no time in going to the Vice-chancellor of the Mysore University and obtaining his permission—written permission, not just an oral go-ahead—to publish the entire work in the journal. In later years Krishnamoorthy published his brilliant translations of Bhāmaha’s Kāvyālaṅkāra and Mammaṭa’s Kāvyaprakāśa in the same journal.

Kannada readers should be eternally grateful to A R Krishna Shastri for his unstinted support to these works that are landmarks in the history of our language. Krishnamoorthy, on his part, offered gurudakṣiṇā by authoring an English monograph on the life and works of A R Krishna Shastri.

Subsequently, H M Shankaranarayana Rao published these translations from Sharada Mandira, his publication label. This marked the beginning of an abiding friendship that went beyond the transactional relationship between author and publisher. Shankaranarayana Rao went on to publish several of Krishnamoorthy’s works, especially his Kannada renderings of Sanskrit treatises on aesthetics. It is a pleasure to read these well-produced works.

Krishnamoorthy joined the Canara College, Kumta in 1953 and worked there until 1959. The college did not have a good library in the initial days. Krishnamoorthy could not take up serious research because of this. In the face of such adverse circumstances, most scholars would have launched a spate of complaints and fallen into inanition. Krishnamoorthy was different. He utilized the limited resources available and translated several Sanskrit plays into Kannada.

L S Kamath, the principal of the college, was impressed with Krishnamoorthy’s dedication to work. He procured Mangesh Ramakrishna Telang’s well-curated Sanskrit library specifically for his use. Krishnamoorthy made the most of it. Armed with the massive knowledge gathered from a close study of an entire library of books, he wrote Saṃskṛtakāvya, a masterly work on Sanskrit literature. He declared in the introduction to this book: “I have not written about any work that I have not studied in the original.” This speaks volumes about his commitment to scholarship.

Saṃskṛtakāvya is as much a scholar’s favourite as it is a connoisseur’s delight. It equips the readers with a keen aesthetic sensibility that is vital to appreciate classical Sanskrit poetry. Dotted throughout with tasteful examples, it introduces the major genres of Sanskrit literature. Krishnamoorthy’s observations on poets are always on the mark. Let me give a couple of examples.

Speaking of Bāṇa’s style, he says:

Elaborate descriptions teeming with various figures of speech form a prominent part of Bāṇa’s wonderful work. If we remove them, the bare story that remains will appeal to children alone. We will then lose an extraordinary poet who competes with Kālidāsa. (p. 296; translation mine)

On the author of Campūbhārata, he observes:

Anantabhaṭṭa was not impressed with Bhoja’s direct and appealing style. He took to an extravagant display of erudition. The invocatory verse of Campūbhārata betrays his love of artificial ideas, compounds and rhymes. [Unfortunately,] later campū writers found Anantabhaṭṭa’s model worthy of emulation. (p. 307; translation mine)

When the Karnatak University in Dharwad established a department of Sanskrit studies, the Vice-chancellor invited Krishnamoorthy to join as professor. He enrolled in 1959 and stayed there until 1984. He brought international fame to the university by his exceptional academic accomplishments. Under its publication tag, he brought out critical editions of Dhvanyāloka and Vakroktijīvita with English translation; edited and published rare works such as Subhāṣitasudhānidhi, Yaśodharacarita and Kavikaumudī; and authored a collection of critical articles on literature and aesthetics titled Essays in Sanskrit Criticism. Apart from writing these books, he guided about twenty-five PhD students.

His only son drowned in a river and met an untimely death in 1973. Krishnamoorthy was shocked and shattered. To overcome the depression caused by this heartrending incident, he plunged into scholarly activities with greater vigour.

In 1984, he joined Satya Sai Institute of Higher Learning in Puttaparti. In a brief span of a few years, he served as the guide to four doctoral students. He moved to Mysore subsequently and lived there until he passed away on 18 July 1997.

* * *

Krishnamoorthy was extremely prompt in his scholarly commitments. If someone wrote him a letter asking a doubt or seeking some clarification, he used to reply in the very next mail. Procrastination was unknown to him. He did not have a single good photograph of himself to print in the proceedings of seminars and conferences. Even after he had attained worldwide renown, there was no telephone in his house. He thought of cars as a luxury and travelled by bus every day. People used to call the bus-stop in front of his house as ‘Krishnamoorthy stop.’ Oftentimes, he used to forget alighting at the right stop because he would be reading a book. The driver or conductor used to prompt him on such occasions. He even had to walk back from afar on many days.

His wife, Smt. Sarojamma, was a pillar of support to him. She took care of their big family with seven daughters all by herself. Krishnamoorthy was always busy with his academic activities. He used to promptly give the month’s salary to his wife and excuse himself from all household work. It was his wife who managed everything – from running the house to marrying off the daughters. To top it all, she had to put up with her husband’s irascible nature! Krishnamoorthy was very fussy with food. He used to fling the plate with anger if, say, the idli was not soft or chutney was too sweet. Sarojamma looked after him like a child.

Many awards and honours came in search of Krishnamoorthy. Chief among them are: Karnataka Sahitya Akademi Award (1973), Karnataka Rajyotsava Award (1989), Uttar Pradesh Sanskrit Academy Award (1985), P V Kane Gold Medal from the Bombay Asiatic Society (1980), Certificate of Honour from the President of India (1978) and the General Presidentship of the All-India Oriental Conference at Rohtak (1994).