The Mysore People’s Convention that convened in Bangalore in December 1919 under the aegis of the Mysore Representative Assembly was largely the result of DVG’s enthusiasm. More than three hundred eminent people hailing from various parts of Karnataka attended the Convention. Some names include M. Venkatakrishnayya, C. Narasimhayya and B. Narasinga Rao, from Mysore, C. Srinivasa Rao and Vasudeva Rao from Chickmagalur, S.R. Balakrishna Rao, K. Shankaranarayana Rao, and C. Subba Rao from Shimoga, S. Venkateshayya and Nanjundayya from Hassan, C.B. Gopala Rao, T. Srinivasachar, and M.S. Ramachar from Kolar, M.R. Nageshwara Iyer, M.P. Somashekhara Rao, Attikuppe Krishna Sastri and others from Bangalore. All of these eminent people played an important part in the deliberations of the Convention. K. Srinivasarangacharya was the head of the Welcoming Committee.

The main objective of the Convention was to examine and discuss the reforms proposed by the Montague Chelmsford Report that had been published just a few days ago. The Chief of the Convention was the retired Deputy Commissioner M. Changayya Shetty.

The following are the key decisions accepted by this three-day Convention: expansion in the civil liberties of the citizens; a place for people’s representative in the Ministerial Cabinet; revision in the Indian political system so that Mysore obtains its rightful place in Indian politics.

DVG also played a key role in organizing the States People’s Conference of the Princely States that was held in Bangalore in 1931. The Princely States were to systematically make way for Representative Government in their dominions; the Princely States had to become partners in the pan-Indian political system and integrate with it—this was the stand taken by the Chairman of the Conference, G.R. Abhyankar, the renowned political philosopher and principal of the Pune Law College.

As the Vice Chairman of the Kannada Sahitya Parishad (1933-38), DVG’s role in expanding the institution’s scope of activities is quite familiar. Therefore it is unnecessary to elaborate this point here. Numerous activities like the Special literary festival, Kannada Teachers’ Training workshop, and Gamaka classes were initiated as the fruit of DVG’s enthusiasm.

DVG offered full encouragement to scores of other initiatives like forming the Karnataka Journalists Association, Shorthand Writers Association, and the Ramayana Publishing Committee.

The Social Service League that DVG had founded in 1915 took rebirth in 1945 as the Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs. Till date, this Institute continues to work towards educating people in order that they become good nationalist citizens and to conduct unbiased study of civic issues. As long as he was alive, DVG was the life-breath of this institution and laboured night and day for three decades to nurture it.

Study Circle

Conducting a study circle every Sunday morning for all our benefit was a work of deep and abiding conviction for DVG. I can’t recall a single day in twenty-five years where he missed it. In the period when the Gokhale Institute was housed in an old building adjoining Pamadi Subbarama Shetty’s house near Netkallappa Circle, on numerous occasions when DVG was suffering from high fever, he would call all of us to his home and imparted lessons in a semi-supine posture in the front room.

Among others, the study of the ten principal Upanishads and the Bhagavad Gita went on unremittingly for several years. The kind of deep and lasting bond that this study developed among DVG and all of us is truly extraordinary. It would transport us to an entirely different world. “kasminnu khalu vijñāte sarvamidaṃ vijñātaṃ bhavati?” “kathamasataḥ sajjāyeta?” It appeared to us as if we ourselves used to ask such lofty questions and seek answers to them on our own.

DVG did not make elaborate preparations before conducting these sessions. He had studied all these philosophical subjects in the traditional manner under the tutelage of “Vidyanidhi” Hanagal Virupaksha Sastri. Plus he was endowed with extraordinary memory. He would expound on the meaning of the Upanishadic verses with us. Complementary verses, analogies, examples from daily life…all these would flash to him without effort, in a torrential fashion. The kind of joy we derived from these expositions is something that needs to be experienced only by listening to them firsthand. All of us who were part of the study circle would eagerly anticipate the arrival of Sunday.

By the time the Bhagavad Gita sessions began, the number of participants had grown to the size of a small assembly. It included numerous Mothers as well. The timing of the study circle was shifted to evening in order to cater to everybody’s convenience.

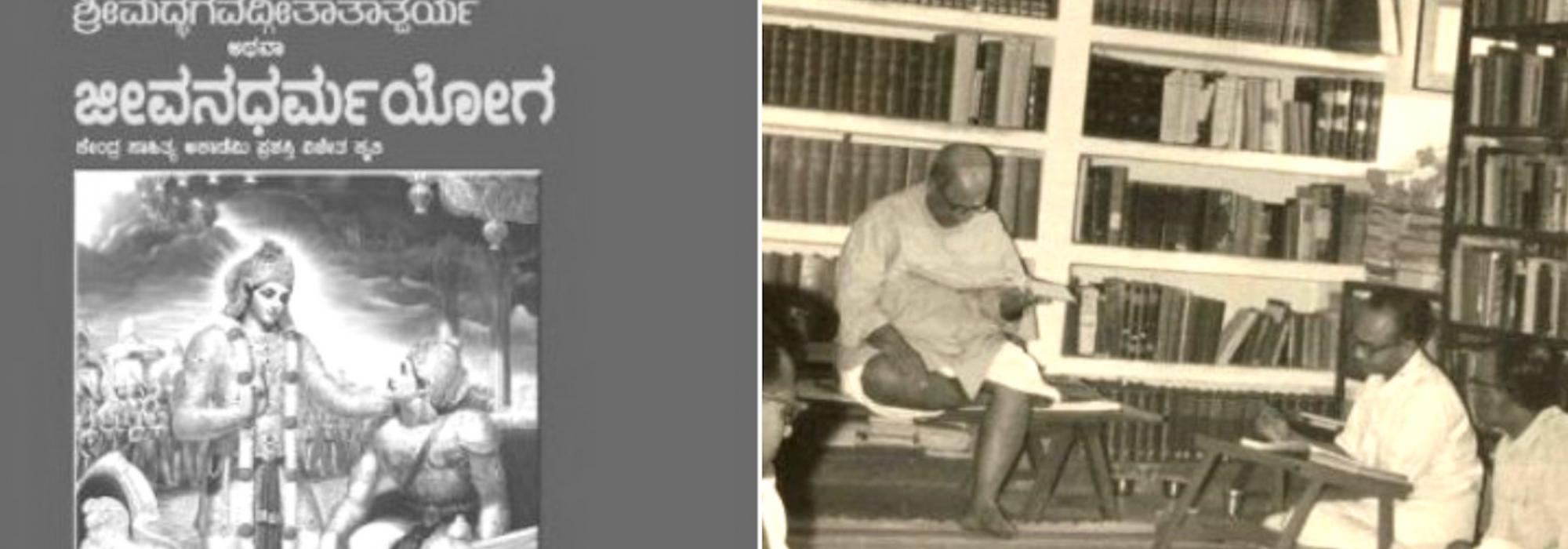

After completing the study of each verse in detail and we revised the entire Bhagavad Gita once more including summaries of each chapter (1962-63). Its collected form is the (Kannada) work Srimad Bhagavad Gita Tatparya [or Jivana Dharmayoga] published by the Kavyalaya publishing house based in Mysore. Prior to this, it appeared as a series in the Kannada weekly, Prajamata.

The various phases during which the proofreading and revision of the text were ongoing were the most enthusiastic and happy days of DVG’s life. This was a lofty work, which was essential for our people – his mind was filled with this feeling of fulfilment. Even as the Bhagavad Gita series was being published each week, the number of letters that DVG used to receive from thinkers and enthusiasts from various towns and cities and villages was innumerable. DVG would unfailingly reply to every single question. In this manner, this became a sort of longstanding Movement which it was never intended to be when it began.

To be continued