What is happiness? It’s hard to define but we all know what it is. We have all experienced it. In fact, we experience it every day – when we eat our food, when we work on a project that we are passionate about, when we smile at someone on the street, when we spend time with a hobby, or when we sleep.

The Hungarian psychologist Mihály Csíkszentmihályi has spent many years studying what makes life worth living and what truly leads to happiness. In his path-breaking work Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience (1990), he discusses the nature of what he calls ‘flow.’ It is a mental and physical state when a person is fully involved with the work at hand and is oblivious of the universe. She experiences great serenity and joy while being totally immersed in the chosen task.

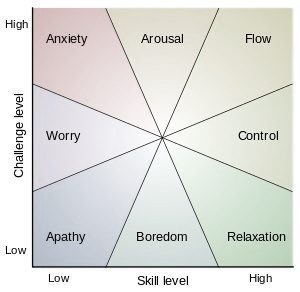

Csíkszentmihályi explains that when a person’s skills are at an advanced level and the challenges that he faces are also high on the scale, he attains ‘flow.’ The states preceding ‘flow’ are ‘arousal’ (when the skills are a tad lesser) and ‘control’ (when the challenges are a tad easier). The other states are not optimal and they don’t lead to happiness. In his 2004 TED talk, Csíkszentmihályi says with a teasing air that a good example for the state of ‘apathy’ is watching television – a task that neither requires skills nor is challenging.

The highest reality according to the Upanishads is brahman, the supreme spirit that is beyond creation and destruction. It is said that everything is a part of the all-pervading brahman (Chandogya Upanishad 3.14.1) and to know brahman is to attain brahman (Mundaka Upanishad 3.2.9). Now, the state of brahman defies definition but the Upanishads describe it with the terms sat-cit-ananda – existence, awareness, bliss. In fact, a whole passage in the Taittiriya Upanishad (2.8.1) is dedicated to explain the nature of bliss in the state of brahman.

We experience this bliss every time we enter a state of deep sleep. But can we experience this lasting bliss while being awake? That is indeed the state of ‘flow.’ When we are immersed in doing an activity that we truly love and have a great deal of expertise, we transition into a refreshing and tranquil state. We get into the zone. (It is worthy to note here that over-indulgence in sensual pleasures gives us an illusion of being in the zone but actually drains our energy.)

After conducting more than 8,000 interviews, Csíkszentmihályi and fellow researchers found seven characteristics of those who are in ‘flow.’ It is interesting to juxtapose each of these characteristics with a related verse from one of the principal Upanishads. For the rishis of the Upanishads, the state of ‘flow’ is the state of brahman, or in other words, the state of being in sat-cit-ananda.

- Focus – We are completely involved in what we are doing. Concentration is at its peak and all our cognitive energy is allocated to the task at hand. In the Taittiriya Upanishad, Sage Varuna tells his son Bhrigu, “Try to know Brahman through penance, for penance is the best means.” (TU 3.2.1) The kind of focus one attains in ‘flow’ closely resembles deep meditation.

- Ecstasy – We have the sense of being outside everyday reality. We feel supreme joy when we do what we love. The Upanishad says, “having performed penance, he [Bhrigu] understood that perfect bliss was Brahman. For it is from that bliss that these beings are born.” (Taittiriya Upanishad 3.6.1).

- Clarity – We have a great inner clarity. We know what needs to be done and we are aware of how well we are doing it. The Kena Upanishad says, “When it [brahman] is known through every conscious state, it is rightly known, and one attains eternal life thereby.” (KU 2.4)

- Confidence – We have an assured self-confidence. It arises not out of arrogance but from the knowledge that we have the necessary skills to do the task. Indeed, this is the great proclamation in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad – “I am Brahman.” (BU 1.4.10)

- Serenity – We have no worries about ourselves and we have a general sense of calmness. Another powerful verse in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad is as follows: “Therefore, he knows it as such, having become calm, self-controlled, withdrawn, patient, and collected, sees the Self in his own self, sees all in the Self... This is the world of Brahman...” (BU 4.4.23) In ‘flow,’ there is a sense of oneness with the universe.

- Timelessness – While being wholly focused on the task at hand, we attain the here and now. Hours seem to pass by in minutes and we forget who we are. “In that state a father is no father, a mother is no mother, the worlds are no worlds, the gods are no gods and the Vedas are no Vedas. In that state, a thief is no thief, a murderer is no murderer...a mendicant is no mendicant, an ascetic is no ascetic. He is not followed by good, he is not followed by evil, for then he has passed beyond all the sorrows of the heart.” (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.3.22)

- Motivation – We are fueled from within and whatever produces ‘flow’ becomes its own reward. It is instant gratification at the highest level. In the Katha Upanishad, Yama tells Nachiketa, “The ignorant pursue outward pleasures, they walk into the wide-spread net of death. The wise, however, recognizing eternal life, do not seek the constant among inconsistent things.” (KU 2.1.2)

A glimpse into the thought process and desires of human beings over centuries yields a startling constancy. Our needs, our emotions, and our fundamental ideas have remained more-or-less the same. The quest of our ancient sages seems to be not so far removed from the pioneering works of modern savants like Jung and Csíkszentmihályi, although they are separated by many miles and years.

All translations of Upanishadic verses are taken from The Upanishads: An Anthology by D. S. Sarma (Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, 1961).

This article was first published in Daily O as part of my column Commonsense Karma.