He had a reasonable awareness of astrology; he had belief too in it; so he examined his horoscope and used to say that the time was a cruel phase for him. But nobody believed it was this cruel.

He was never fully fit and healthy; even when I first saw him (1904), he had the appearance of being weak due to suffering from constipation and skin ailment. However, by the time he arrived in Bangalore (1916), he gradually improved and was quite healthy though not fully fit. In matters of food and snacks, he could compete, challenge, participate and thoroughly enjoy himself. He used to love huḻitovve; but after he moved to Mysore (1927) the climate there did not suit him; his digestion weakened, he developed piles and it impaired his body. By his last days, even that was cured by a traditional doctor; but his physical stamina was weakening. During this time, his weariness increased due to fatigue, and cold and windy weather brought him down with fever. The fever progressed and turned into pneumonia. His normally weak lungs and heart became even weaker and his body started shrinking day by day. “There are no symptoms of any disease; everything is normal; there is weakness of the heart; he is exhausted; he will gradually recover” - this was everyone’s hope; seems like even he did not realize that the end was near; but his life was extinguished unexpectedly. Sorrow enveloped all.

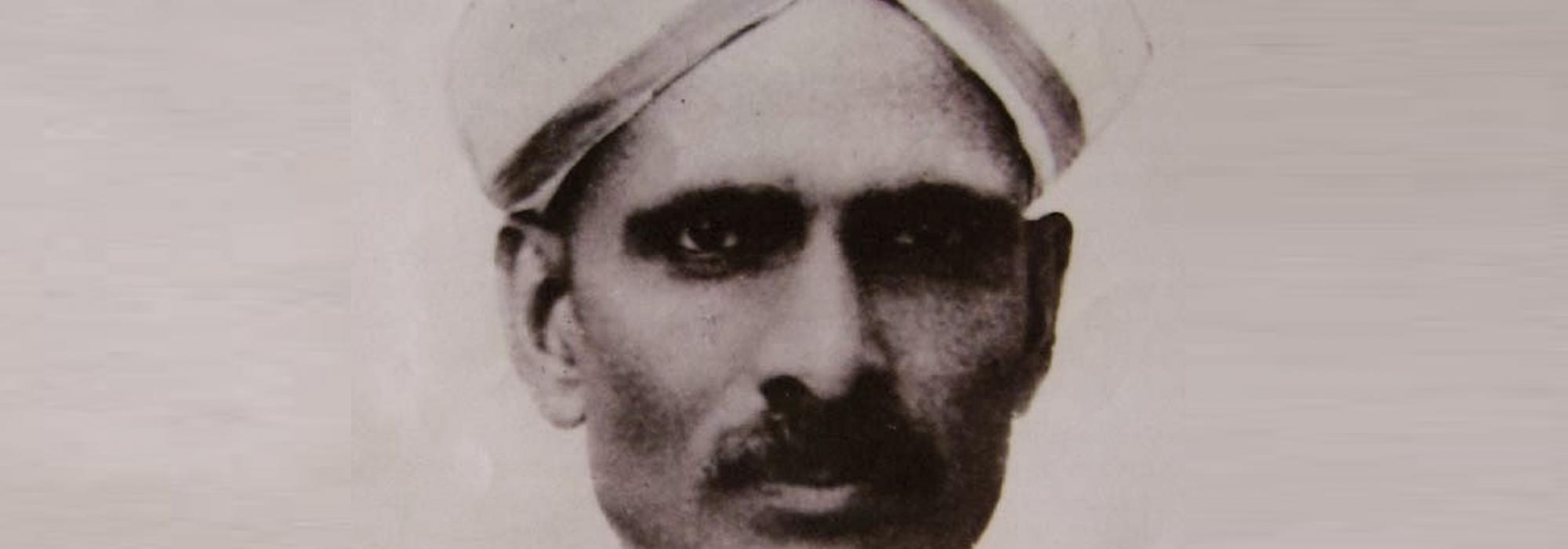

One trait of Venkannayya that was visible throughout was his soft nature. It would be right to say that this was his birth trait, though he grew up also inculcating worthy companionship, responsibilities due to situations, introspection and contemplation. That is why he was valued by all since a young age. When he first came to Mysore he lived in a hotel for nearly a year. Even there, everyone treated him with affection; the attendant there tended to him (Venkannayya) while he was suffering from ill health, gave him extra ghee and buttermilk, bathed him, cared for him, served him snacks and appeased him. At that time he was in no position to pay and earn affection. In any case, money does not guarantee affection. Being soft-spoken, gentlemanly behaviour, and his cheerful face - these mattered more than money.

He did not believe in destroying evil people. “Assisting the wicked (to mend their ways), and respect towards the good” was the root mantra of his conduct. He used to say - if evil people reform through friendship and gentleness, let it be, else it is unnecessary to do it in an unpleasant manner. “If a thorn jabs the leg, let it rot and heal itself, why pierce it and end up with foot ache?”. ध्रुवं स नीलोत्पलपत्रधारया शमीलतां छेत्तुमृषिर्व्यवस्यति (...indeed he uses the tender lily leaf to cut the hard śamī bark.) - Duṣyanta can complain like this. But Kaṇva knew his course; that is why he remained a Ṛṣi. This manner of attitude and behaviour comes not easily to this body that consumes everything. He used to punish his mind repeatedly, swallow his anger repeatedly to pursue his goals. Since this was a conscious struggle, its awareness grew day by day, and during his last days he used to say “seems like I am old; I am highly irritable and not peaceful”. But everyone who observed him knew - how peace, friendship, and contentment were growing.

The most difficult part of being composed is the hold on one’s tongue; in the matter of topics that need to be kept secret, it is difficult to hold one’s tongue and not utter a word; Venkannayya had learnt it very well. He was an example for “ಮಾತು ಆಡಿದರೆ ಹೋಯಿತು. ಮುತ್ತು ಒಡೆದರೆ ಹೋಯಿತು” (‘the word once uttered never comes back, the pearl destroyed never becomes whole’). His nature was to speak a little less than what was necessary for apprehension that what was said would be construed differently, amplified and spread. It was impossible even for his close associates to understand the full extent of what was in his mind. So, in a way he was secretive (close mouthed). However, this did not diminish his friendship, simplicity or affection; With those he wanted, he could converse about other topics for any length of time; he would generate an intimate feeling in the course of conversation.

Along with his rich scholarship in Kannada and English literature, Venkannayya had good familiarity with Telugu and Bengali as well as an adequate familiarity with Tamil and Sanskrit. He penned a life history of Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa for Sri Ramakrishna Mutt, based on Bengali-language books; he translated a section of Śrī-rāmakṛṣṇa-līlā-prasaṅga; he translated several literature related essays of Ravindranath Tagore to Kannada and published them in ‘Prabuddha Karnataka’. He was acquainted with the Upanishads. He used to chant Vālmīki-rāmāyaṇa, Adhyātma-rāmāyaṇa and Bhagavad-gītā in a choked voice with tears rolling down. He has penned a few articles on the history of Kannada literature for ‘Sahitya Parishatpatrike’ and some for ‘Prabuddha Karnataka’. He researched and edited ‘Hariścandra-kavya-saṃgraha’, ‘Kādambarī-saṃgraha’, ‘Basavaraja-devara-ragaḻe’ and wrote a masterly foreword to ‘Kādambarī-saṃgraha’ and ‘Basavaraja-devara-ragaḻe’. He has authored the sections on ancient Kannada grammar and the section on history of the language for ‘Kannada Kaipidi’. He has contributed to the editing of the ‘Pampabharata’ published by the Parishat and in editing ‘Kumārvyāsa-bhārata’ published by the Oriental Library. He has researched ‘Siddarama-purāṇa’ and readied it for printing (This was published in 1941 by Karnataka Sangha of Shivamogga). He aimed to publish ‘Kumārvyāsa-bhārata’ as a neat and pristine single volume edition. For this purpose, he procured an ancient edition and produced a paper copy. But due to increase in other workload and day-to-day essential activities, he could not give attention to this.

In summary, he lectured more than he wrote. But both in his lecture and in his writing, there was a unique character. He would refine it well, make it non-controversial and use it on a factual basis. There is neither ambiguity nor embellishment in it. As one of our venerable friends jocularly used to say again and again, “there is no taḻuku (‘glitter’ in Kannada) in Taḻuku (The T in T S Venkannayya stood for Taḻuku, his ancestral village) Venkannayya” - this was aptly applicable to Venkannayya’s writing. It would not be possible to remove, add or otherwise modify anything in it. He had grasped very well the responsibilities of writing; hence he would not easily agree to requests for authoring; he never craved for authorship.

Venkannayya’s superior writing, his oratory more than his writing, his conduct more than his oratory, his character more than his conduct - these will remain in the hearts of those who knew him; his memory will live forever among Kannadigas.

Venkannayya was fortunate; he was a good person as long as he lived, was recognised as one, led a smooth and refined life, nurtured prosperity and relationship, pleased both God and men, and moved on. But his associates and friends were not lucky enough to have him amongst themselves a little longer.

(Prabuddha Karnataka, Issue 78, 1939).

This is the final part of the three-part translation of the article "ದಿವಂಗತ ಶ್ರೀಮಾನ್ ಟಿ ಎಸ್ ವೆಂಕಣ್ಣಯ್ಯನವರು" by A R Krishna Sastri which appears in the collection "ಬೆಲೆಬಾಳುವ ಬರಹಗಳು". Edited by Raghavendra G S