In modern times, the river of Indian aesthetics flows between the banks of two intellectual giants: M Hiriyanna and V Raghavan. Hiriyanna presented its unadulterated essence in an unalterable form. Raghavan ransacked the sources and traced the historical development of its fundamental tenets. The former illumined the summit; the latter outlined various paths that lead to the summit. K Krishnamoorthy represents the best of both. To extend the river metaphor, he bridges the two banks and enables easy access to both. His works represent the ideal combination of depth and detail.

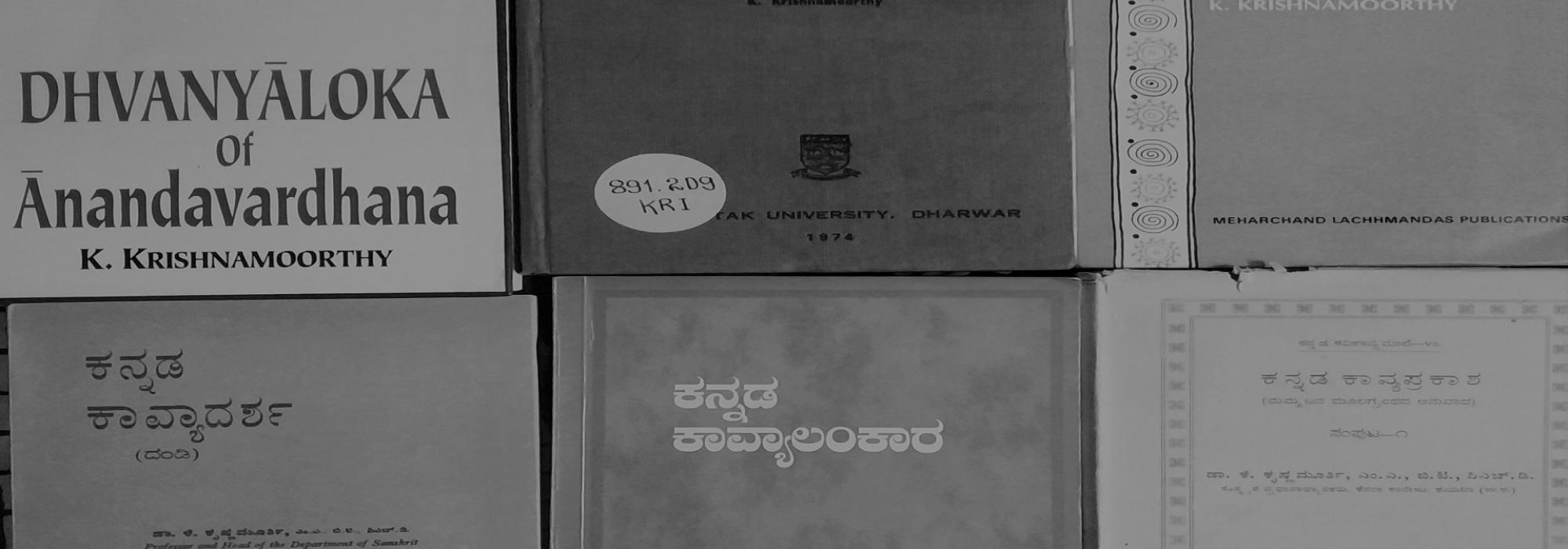

He authored more than seventy books in Kannada, English and Sanskrit; brought out monumental editions of Dhvanyāloka and Vakroktijīvita; and translated all the major works of Indian aesthetics from Sanskrit into Kannada. The number of book reviews, encyclopaedia entries, popular essays and research articles he wrote far exceeds a thousand. Though he was well-informed in Prācīna-nyāya, Vyākaraṇa and Vedānta, Krishnamoorthy dedicated his entire life to the study of a single subject – Alaṅkāra-śāstra. He upheld the ancient saying, ‘Ekasmin janmani ekaṃ śāstram.’

* * *

[[{"fid":"10329","view_mode":"default","fields":{"format":"default","alignment":"left","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"K Krishnamoorthy","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"K Krishnamoorthy"},"type":"media","field_deltas":{"1":{"format":"default","alignment":"left","field_file_image_alt_text[und][0][value]":"K Krishnamoorthy","field_file_image_title_text[und][0][value]":"K Krishnamoorthy"}},"attributes":{"alt":"K Krishnamoorthy","title":"K Krishnamoorthy","style":"width: 239px; height: 300px;","class":"media-element file-default media-wysiwyg-align-left","data-delta":"1"}}]]Krishnamoorthy was born on 30 July 1923 in Keralapura, a small town on the banks of the river Kaveri in Karnataka. He hailed from a Sanketi brāhmaṇa family. His parents were N Venkatasubbayya and Gowramma. Venkatasubbayya was a schoolteacher with a good knowledge of Sanskrit and Kannada. It seems that he had passed the Kannada paṇḍita-parīkṣè but had not got the title because of some technical issue. He did not take up the exam again but wished to see his son grow up to be a scholar. To this end, he taught Krishnamoorthy the rudiments of grammar and made him learn by heart Aṣṭādhyāyī, Amarakośa and Śabdamañjarī at an early age. Later, when Krishnamoorthy appeared for the paṇḍita-parīkṣè, his father made him memorize foundational texts of Kannada such as Śabdānuśāsana and Śabdamaṇidarpaṇa.

Thus, Venkatasubbayya laid a strong foundation for his son’s scholarly pursuits. He bequeathed to Krishnamoorthy not material wealth but imperishable virtues: meticulousness, perseverance and a sharp sense of self-worth.

Krishnamoorthy passed the lower secondary examination in Arkalagud, Hassan, and moved to Mysore to get enrolled in Banumayya Highschool. Life in the new place was challenging. All these years, loving parents used to take care of all his needs. He was used to delicious dishes prepared by his mother. Now, suddenly, he had to fend for himself. Because he was poor and could not afford food, he had to take meals in the homes of friends, acquaintances or considerate strangers. He used to take turns in visiting various people who were kind enough to have him over on some days of the week. This practice was known as vārānna in those days. To escape from the mental turmoil caused by poverty, Krishnamoorthy immersed himself in studies. He passed the SSLC examination with flying colours.

At the intermediate level, he studied Kannada, English, logic and history. He chose Sanskrit as the optional subject because it fetched him a scholarship. Krishnamoorthy’s entry into Sanskrit was a fortuitous affair forged by an acute financial condition. (This is true of many yesteryear traditional Sanskrit scholars.) He studied with single-minded focus and stood first in the examination. He was the only student to secure a first class in Mysore that year.

In the BA Honours course, he wished to study English but chose Sanskrit to avail the fee waiver offered to Sanskrit students. The syllabus was extensive and included various systems of knowledge. Siddhāntakaumudī was the prescribed text in grammar. Krishnamoorthy found the lessons on this treatise woefully inadequate. Because perfunctory understanding did not satisfy him, he sought his father’s help. Venkatasubbayya did not feel up to the mark to teach himself. He took his son to one Tippuru Subbaraya Shastri, a neighbour and relative. He had studied grammar from Ramakrishna Shastri, the father of the renowned Kannada littérateur, A R Krishna Shastri. Although he did not have anything to do with grammar for more than three decades, he was confident that his Guru’s grace would not fail him! Over a few months, he managed to give a comprehensive overview of the Pāṇinian system. In later years Krishnamoorthy would fondly remember the thorough instruction he received from Subbaraya Shastri, which was of immense help in his academic career.

He enrolled for postgraduation in Sanskrit and completed it in 1943. He stood first even here. It seems that the record he set was unheard of in the past twenty years and was not surpassed in the next eighteen years! Because he did not get a job immediately, he undertook the BT course and secured the academic qualification to be a teacher.

Krishnamoorthy had appeared for the Kannada paṇḍita-parīkṣè during his intermediate and undergraduate days. The exam included a paper on classical versification for fifty marks. Since Venkatasubbayya wanted his son to do well, he took him to Ganjam Krishnappa, a traditional scholar, to learn the nuances of composing verses. On the first day the teacher taught the building blocks of versification. At the end of the three-hour class Krishnamoorthy had managed to compose a couple of verses in the kanda metre. He was extremely unhappy with this paltry outcome. On the way home, he thought: “Our ancient poets would not have struggled like this—huffing and puffing at every step—to compose verses. The secret remains elusive. Let me try to discover it myself.”

That night after dinner he locked himself in a room and studied the poems of Pampa, careful not to miss a single detail. In a couple of hours, he had unlocked the mystery of the kanda metre – its rhythm, the pattern of mātrās in it, the placement of the crucial ja-gaṇa, and so on. He swiftly composed more than ten verses and showed them to his father. Venkatasubbayya was overjoyed.

Krishnamoorthy was the victim of academic sabotage at the very beginning of his career. He did not get a job in Mysore despite his impressive educational record. Then A R Krishna Shastri came to his rescue. He wrote a letter to his friend S C Nandimath, recommending Krishnamoorthy’s name for the lecturer’s post in Basaveshwara College, Bagalkot. Krishnamoorthy joined the college in 1944. He used to teach for hours on end without a break. Soon, he distinguished himself as a good teacher and a first-class researcher.

In those days, scholars could independently secure a PhD from Bombay University by submitting a thesis, without undergoing regular coursework under a supervisor. K R Srinivas Iyengar, the well-known professor of English, encouraged Krishnamoorthy to apply for it. He gave him the confidence to write in English. Following his advice, Krishnamoorthy began to write on Ānandavardhana’s Dhvanyāloka. Alongside teaching students from 11 am to 5 pm, he wrote around ten pages every day and completed the thesis in two months!

I can only imagine the kind of effort he should have put in. There was no time to read, make notes on various topics, classify them, discuss intricate issues with scholars, publish findings in journals, get perceptive feedback, rework the tricky portions, and so on. He had to depend on his own understanding and conviction. His thesis was titled The Dhvanyāloka and its Critics. It extended to 470 pages. This remarkable academic feat brought with it a wonderful upaphala – the first-ever English translation of the entire Dhvanyāloka!

The examiners of this thesis were P V Kane and H D Velankar – phenomenal scholars whose very names were enough to scare the living daylights out of namesake academicians. These literary titans gave their learned opinion that Bombay University could confer the PhD degree on Krishnamoorthy without conducting a viva voce. The thesis had included a critique of P V Kane’s position on the authorship of the Dhvanyāloka. However, this did not stop the great scholar from commending it. Such intellectual integrity ennobles the pursuit of academics, which is usually only a cerebral exercise.

Krishnamoorthy was the first person in the Mysore State to secure a PhD in Sanskrit (1947).

He had the good fortune of receiving guidance from M Hiriyanna at a critical juncture. Krishnamoorthy’s father gave a copy of his PhD thesis to Hiriyanna and sought his invaluable feedback. This probably happened a couple of years before the great scholar’s demise. Despite his physical ailments, Hiriyanna read the thesis with great attention and sent for Krishnamoorthy after eight days. He asked searching questions, quoted from Indian and Western authorities and explained that the connoisseur is the locus of aesthetic experience.

Krishnamoorthy basked in the warm glow of Hiriyanna’s carefully cultivated scholarship and unfailing insight into the subject. What are the sources to consult, how to collect and sift data, how to develop and present an argument – the master had answered all these questions without Krishnamoorthy posing them. Hiriyanna advised the boy to divide his thesis subject-wise into several parts and publish them in academic journals. He believed that publishers would later come forward to bring it out as a book. This brief interaction helped Krishnamoorthy emerge as an exceptional scholar.

In the same year, Bombay University revised its guidelines for academic designations. The institution in which Krishnamoorthy used to work came under it. Accordingly, it changed his designation from professor to lecturer. Krishnamoorthy was incensed by this demotion. He resigned from the job at once and returned to Mysore. To support his family, he translated Sanskrit plays such as Nāgānanda and Ratnāvalī into English. He wrote under a pseudonym ‘Dr. Banerjee’ for a publication label called Maruti Book Depot.