Mallinātha has made some insightful observations in commenting on this verse. According to him, there were pictures in the mansion of various episodes from the time that Rāma and Sītā spent in the forest. Among them were paintings that depicted Sītā’s abduction, Rāma’s lament, his search for Sītā, and so on. When Rāma and Sītā looked at these and mulled over the episodes once again, they were neither sad nor disturbed; instead, they were happy.

This episode throws light on some seminal aspects of aesthetics. Only a brahmajñānī, a person endowed with ultimate realization, can experience the world as poetry. To do so one must have overcome the bonds of avidyā. To the general run of people, art exists within the confines of the world – it is a savoury something that remains untouched by personal likes and dislikes. During art experience, desire and strife cease to exist, while the ignorance of the ultimate truth persists. In other words, kāma and karma get eliminated temporarily while avidyā endures. Prof. M Hiriyanna has explained this process in a masterly manner.[1] The seed of desire remains latent in an individual when it does not manifest as action. It does not bother the connoisseur during art experience. To arrive at that feeling, a connoisseur should partake of art leisurely, with an undisturbed mind. One cannot experience art well in a hurry, with a mind tormented by thoughts. Abhinavagupta has touched upon some of these aspects that hinder art experience in his exposition of rasa-vighnas.

In the present context, Rāma and Sītā are happily settled in Ayodhyā, having overcome a variety of troubles. They have at their disposal all amenities that would comfort their senses. Mere hedonists would be happy with indulging in such comforts. On a level higher are the connoisseurs who seek to satisfy not merely the five external organs but also the mind, the internal organ. The poet here suggests that Rāma and Sītā sought such satisfaction in looking at the pictures. Interestingly, the subject of the pictures were their own lives – specifically, events that had caused them terrible pain a few years ago. Generally, people turn sad when they recollect bitter moments from the past, even if they are happy now. Some others might not be sad but would take pride in the fact that they have crossed all the troubles. These two reactions, respectively, stem from tamas and rajas. On the other hand, people rooted in sattva will enjoy the memories of unhappy events. What gives impetus to such people is a work of art that makes even sad events seem enjoyable. As we have observed previously, undiluted ānanda—which is different from the mundane pain and pleasure—emerges when the worldly chain of causes and effects transforms into an aesthetic sequence of vibhāvas and anubhāvas. Some of our elders describe this ānanda as sukha, prīti, and so on, without knowing the exact technical word. Kālidāsa has brought out all these details beautifully.

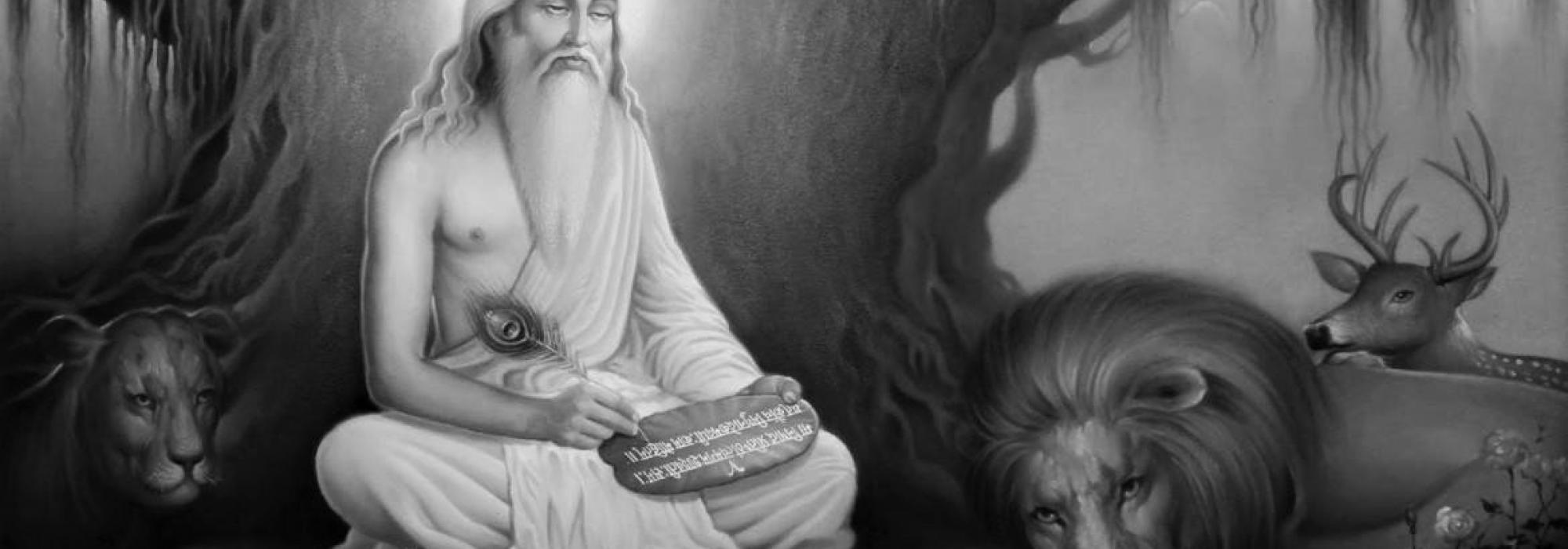

The poet introduces Vālmīki to great aesthetic effect when Sītā, abandoned by her husband, lies morosely on the forest ground:

तामभ्यगच्छद्रुदितानुसारी

कविः कुशेध्माहरणाय यातः।

निषादविद्धाण्डजदर्शनोत्थः

श्लोकत्वमापद्यत यस्य शोकः ॥ (१४.७०)

The poet who had set out to collect darbha and samidh [required for rituals] came to Sītā following the sound of her sobs. [Previously,] his grief upon seeing a bird being killed by a hunter had expressed itself as a verse.

This is a first-rate verse. Not only does it appeal as poetry; it also gives insights into aesthetics. Kālidāsa has tacitly drawn our attention to one of the defining traits of poets – responsiveness. A person who does not respond to the happy and sad happenings of the world is far from being a poet; he does not even count as a human. Empathy and responsiveness mark out good people. Wise are those who observe these in practice and strive to achieve peace and harmony as a result. A poet limits himself to expressing these thoughts through words. Here we have Ādikavi Vālmīki who embodies all the traits of the ideal person and the ideal poet that we have discussed thus far. That is why he is hailed as a ṛṣi-kavi, a seer-poet. The epithet kavi applies to him in both senses of the word: (i) an enlightened individual, as used in the Vedas and (ii) a creator of poetry, as used in literature.

Because Kālidāsa knew this well, he has used the word kavi not merely as an adjective but as a noun. This is not a one-off example; the poet has used the same word to refer to Vālmīki in three other instances.[2] All adjectives are adjuncts. Nouns are not. They are the foundation for adjuncts. In referring to Vālmīki as a kavi in the said manner, Kālidāsa has pointed at the ideal that all poets must strive after. It is unfortunate that our writers on poetics do not discuss these aspects of an ideal poet. We should shower praise on Kālidāsa who has pointed at the ideal, keeping aside his self-esteem as a poet. We get an actual picture of Kālidāsa’s personality when we view this verse vis-à-vis his description of himself as a dullard seeking fame as a poet.

In closing this section we can confidently say that Kālidāsa is not just the poet who continued the legacy of Vyāsa and Vālmīki; he is also the master of aesthetics who guided Ānandavardhana and Abhinavagupta.