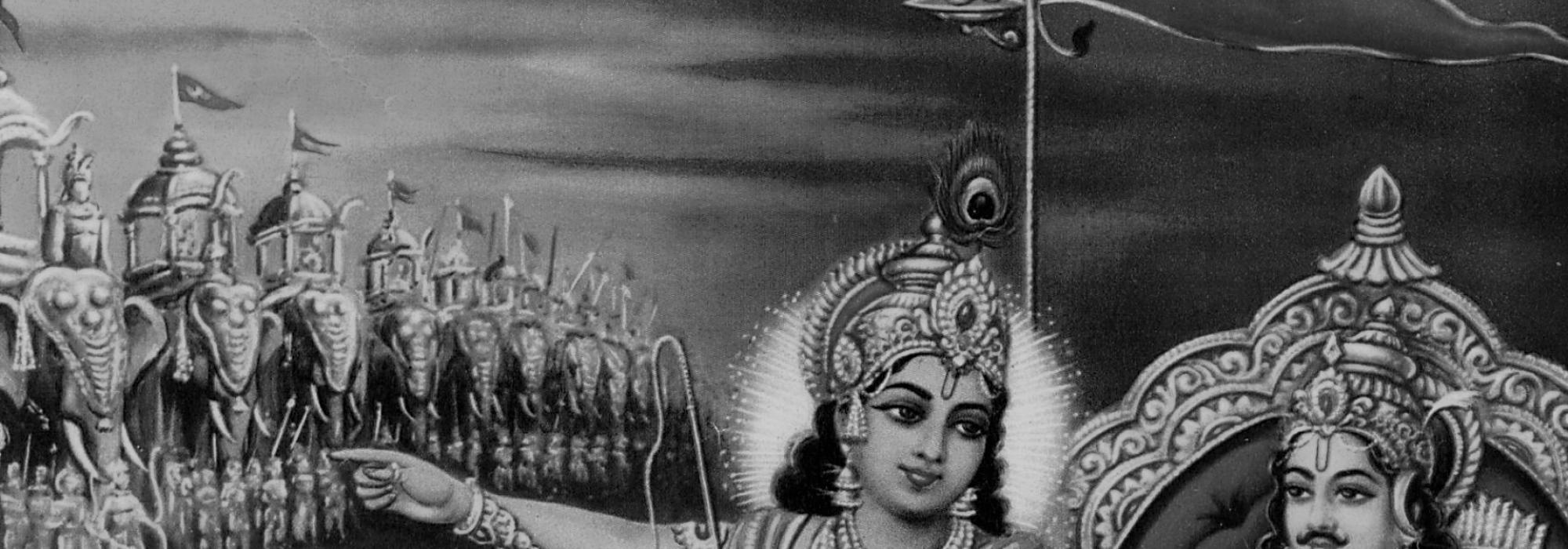

The epics and mythology of a culture deeply influence art and literature. This is pronounced in the case of India, as our heritage still has the unbroken, living tradition of the sublime epics and their fascinating stories. For close to three millennia, our culture has drawn inspiring themes from these perennial sources, thus perpetuating their metaphorically powerful and aesthetically elevating expressions. All art forms of India—irrespective of distinctions like classical and non-classical, traditional and modern—are indebted to our extraordinary epic heritage. It is quite natural to explore this for the purpose of film-making. India still enlivens and celebrates its past and so it is no wonder that even a modern medium like movie-making was inspired by mythology. India’s first ever celluloid venture Raja Harishchandra (1913) of Dadasaheb Phalke is based on the story of a king from the solar dynasty, a torchbearer of truth, a theme that finds its roots in the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa (Ṛgveda), Devībhāgavata Purāṇa and the Rāmāyaṇa. The science and art of film-making is a natural expansion of the centuries old theatrical tradition, so most of the movie-makers directly translated their skills of stagecraft on to the silver screen. In this process, it is likely that both the pros and cons of theatrical art infiltrated the celluloid craft. This is understandable—and, to an extent, agreeable—as the art of movie-making was still in its infancy.

As with other Indian languages, Kannada cinema too started off with ‘talkies’ made with mythological themes. Experts opine that it was natural to people of those days to embrace such films and even then the interests of the box-office could not be ignored. This perhaps was the reason for a rich harvest of mythological movies in the early decades of Kannada cinema. This holds true with other languages as well. But among the two thousand plus ‘talkies’ that have been produced in Kannada since 1934, hardly fifty or sixty movies were made based on our epic mythology until 2000. Later, in these seventeen years (up to April 2017), no more such films have been produced. In the past eighty-three years, less than three percent of the movies have had a mythological theme; the number of mythological films drastically decreased year by year and decade by decade. This fact can be verified by looking at the ratio of the total number of films that were produced in every year/decade against the number of mythological movies that were made in the respective period.

In the present article, statistical details are not elaborated, as the emphasis shall be on the aesthetics and cultural philosophy that work behind film-making in Kannada. We will, however, study this topic by comparing it primarily with Telugu cinema. This consideration is not out of place, for the Telugu film industry has produced the maximum number of mythological movies in India, and most of them being of a high quality. As languages, Kannada and Telugu have many similarities, which include aspects of culture and aesthetics. Furthermore, even the traditions of movie-making in these languages are similar. Just one instance of the many similarities: films of both languages were produced in an alien location (Chennai, which was then Madras).

The production of movies based on epics and their mythology suffered badly with the advent of television serials of the same kind. This started from the mid-1980s. The negative effect further snowballed upon the arrival of private TV channels, and grew increasingly worse with website like YouTube coming into the picture. The younger generation have generally been uninterested in mythological themes, unlike the older generation, who met their humble demands through small screens. Theatres found it hard to screen such movies.

The following is a list of the available mythological movies in Kannada, broadly classified according to their sources and themes:

- Movies based on the epic Rāmāyaṇa:

Satī Sulocana (1934), Mahirāvaṇa (1957), Vālmīki (1963) and Śrī Rāmāñjaneyayuddha (1963). All these films, though based on the characters created by the seer-poet Vālmīki, draw the storyline from different versions of the epic such as Adhyātma Rāmāyaṇa, Ānanda Rāmāyaṇa and Śeṣa Rāmāyaṇa. They even rely upon popular folk stories and independent creations of comparatively recent poets.

- Movies based on the epic Mahābhārata:

a. Films based on the main story and/or characters of the epic:

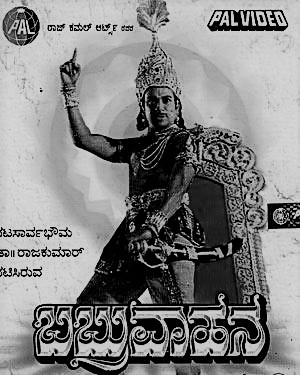

Rājasūya-yāga (1937), Subhadrā (1941), Śrīkṛṣṇagāruḍi (1958), Nāgārjuna (1961), Subhadrākalyaṇa (1972), Mūrūvare Vajragaḻu (1973), Babhruvāhana (1977) and Beraḻge Koraḻ (1987)

b. Films based on the sub-stories of the epic:

Candrahāsa (1947), Tilottame (1951), Kaca-devayāni (1956), Naḻa-damayanti (1957), Satī Naḻāyani (1957), Satī Sāvitri (1965) and Satī Sukanyā (1967)

Many of these films do not adhere to the original epic of the sage-poet Vyāsa in every detail. They heavily draw from other minor versions that are found in Purāṇas and folk traditions. Sometimes, the scriptwriters of films themselves take the liberty of coming up with novel deviations from the epic. Movies like Śrīkṛṣṇagāruḍi, Nāgārjuna and Mūrūvare Vajragaḻu in Section (a) and Tilottame and Satī Naḻāyani in Section (b) are classic examples of this trend. Stories of these films, borrowed from the purāṇic and folk sources, were already established in the traditional and professional theatrical practices. Sometimes different textual variants in the original epic themselves would have been the cause for such deviations. Indeed, such deviations from the original epic or taking such liberties with the main plot can be seen not just in Kannada films, but also those in other languages. This is not even a modern trend, as many poets of high merit who composed in classical Sanskrit—including Bhāsa, Kālidāsa, Diṅnāga and Bhavabhūti—have similarly innovated while adopting the epics for their plays and poems. Even the various recensions of the great epics stand as a testimony to this.

- Movies based on the stories of Purāṇas such as the Bhāgavata, Devībhāgavata, Kūrma, Padma, Viṣṇu, Śiva, Skānda, and Hālāsya.

a. Films based on vaiṣṇava themes:

Kṛṣṇa-sudhāma (1943), Rādhāramaṇa (1944), Kṛṣṇalīlā (1947), Śrīkṛṣṇakalyāṇa (1952), Daśāvatāra (1960), Mohini-bhasmāsura (1966), Śrīkṛṣṇa-rukmiṇī-satyabhāmā (1971) and Śrīnivāsakalyāṇa (1974)

b. Films based on the devotees of Viṣṇu:

Bhakta Dhruva (1934), Haribhakta (1956), Prahlāda (1942), Bhakta Prahlāda (1958) and Bhakta Prahlāda (1983)

c. Films based on the Śiva-śākta themes:

Mahānanda (1947) / Śiva-pārvatī (1950), Bhūkailāsa (1958), Mahiśāsuramardinī (1959), Gaṅge-gauri (1967), Pārvatī-kalyāṇa (1967), Cāmuṇḍeśvarī-mahime (1974) and Śabarimale Svāmi Ayyappa (1990)

d. Films based on the devotees of Śiva and Śakti:

Ciranjīvi (1937), Hariścandra (1943), Beḍara Kaṇṇappa (1954), Bhakta Mārkaṇḍeya (1956), Ohileśvara (1956), Satya-hariścandra (1965), Bhakta Siriyāḻa (1980), Śivabhakta Mārkaṇḍeya (1987), Śiva Meccida Kaṇṇappa (1988) and Śivalīle (1996)

e. Films based on the themes of great women who were devoted to their husbands:

Sati Tuḻasi (1949), Reṇukā-mahātme (1956), Mahāsati Anasūyā (1965), Mahāsati Arundhatī (1968) and Śrīreṇukādevi-mahātme (1977)

f. Films based on the glory of other gods and their devotees:

Rājā Vikrama (1951), Rājā Satyavrata (1961) and Śaniprabhāva (1977)

When we look into the nature of films in this section, we are wonderstruck by the liberties the scriptwriters and directors have taken with the original theme. More than the lives and passions of the gods and goddesses, their devotees’ stories of plight—especially regarding the pātivratya of women—attracted the film-makers. Needless to say, this indicates the demands of the box-office. The trials that devotees underwent in their spiritual journey were of great commercial interest, since these emotionally charged sequences particularly attracted rural women. It is also true that some of the movies in this section are essentially heart-touching, and are of a high merit, judging from criteria such as script, dialogues, lyrics, music and acting.

In the above classification, the movies that are not based on Purāṇas and yet deal with the glories of various gods and god-men, their holy places, and lives and miracles of their devotees have not been considered for obvious reasons. A few examples of the movies of this sort are: Maṅgaḻa-gauri (1953), Devakanyakā (1954), Śivaśaraṇe Nambiyakka (1955), Svarṇa-gauri (1962), Sati-śakti (1963), Śrīdharmasthaḻa-mahātme (1962), and Śrīkanyakā-parameśvarī-kṛpā (1966). Even the films based on the lives of historically renowned god-men and devotees like Basavaṇṇa, Allamaprabhu, Purandaradāsa, and Kanakadāsa are not considered, for they do not belong to the epic mythology genre.

With this working data, we can now make some observations: Though there are a few films in Kannada produced on the basis of the Rāmāyaṇa and Mahābhārata, not a single attempt has been made to handle their complete story. This is not, however, the case with Telugu cinema. There are quite a number of movies produced that take into account the complete storyline of the epics. Noteworthy ones are the Sampūrṇa-rāmāyaṇas which have ably covered the whole story of Rāmāyaṇa. Titles like Śrīrāmajananam, Sītākalyāṇam, Sītā-rāma-kalyāṇam, Vālmīki, Brahmarṣi Viśvāmitra, Padukā-paṭṭābhisekam, Śrīrāma-paṭṭābhiṣekam, Vira Hanumān, Sītā-rāma-vanavāsam, Lava Kuśa, Śrīrāma-rājyam and Śrīrāmāñjaneya-yuddham, in spite of covering the story in parts, are not without a logical completion. Even the Tamil and Hindi film industries have attempted to bring in the complete storyline of Rāmāyaṇa in their own productions, however insignificant they may be. But in Kannada, we find two songs (one in Bhūkailāsa and the other in Vālmīki) that try to narrate the complete story of Rāmāyaṇa in a nutshell.

Coming to the other epic, the Mahābhārata, the situation is more pathetic. We do not even find a song that captures the spirit of its story. But in Telugu, though we do not come across a single film that covers all major events of the epic (none of our theatrical productions or classical plays or even modern movies in various languages have attempted such a herculean task), quite a few movies are made, which can make up the whole story, when taken sequentially.

Films such as Bhīṣma, Ekalavya, Bāla-bhāratam, Śrīkṛṣṇa-pāṇḍavīyam, Śrīkṛṣṇārjunīyam, Pāṇḍava-vanavāsam, Nartanaśālā, Śrīkṛṣṇa Rāyabhāram, Śrīkṛṣṇāvatāram, Kurukṣetram, Vīrābhimanyu, Dāna-vīra-śūra-karṇa, Śrīkṛṣṇārjuna-yuddham, Babhruvāhana, and Māyābazār have not only connected the original story leading to its completion, but also portrayed the main characters in a brilliant manner. Apart from this, the sub-stories that are not connected to the main theme are also well-recreated in the following films: Kaca-devayāni, Śakuntalā, Satī Sāvitrī and Naḻa Damayantī.

Based on Harivamśam, the appendix of the epic Mahābhārata, and along with other purāṇic sources like the Viṣṇu, Bhāgavata, Padma, and Brahmavaivarta, the story of Krishna is profoundly delineated through many films in Telugu. Yaśodā-kṛṣṇa, Śrīkṛṣṇalīlālu, Śrīkṛṣṇavijayam, Śrīkṛṣṇa-tulābhāram, Śrīkṛṣṇa-satya, Dīpāvali, Uṣāniruddham, Prabhāvatī-pradyumnam, Śrīkṛṣṇa-kucela are Śrīkṛṣṇāñjaneya-yuddham are but a few examples.

Apart from the two great epic stories, other mythological themes are also handled by the Telugu film industry, for instance, movies made on Śiva, Viṣṇu, Devī, and Gaṇapati. We also find a lot of films that are just aimed at the box-office by playing on the sentiments of the laity. Unfortunately, in Kannada, such pseudo-mythological films, having no regard for the epic-feel and merely catering to the masses by employing cheap miracles, childish wonders and superficial devotion came to the forefront, and directors never really took to the sublime. The epic standards of Telugu movies are markedly better than those of Kannada and other languages. As the main stories of the epics were not employed to a great extent, the sublime drama and the grand emotional clash seen in their plots and characters could not be exploited by Kannada movie makers.

Though the characters are almost the same, plots are seemingly common and the overall mythological feel is similar, a sensitive mind can easily identify qualitative differences between the epics and the Purāṇas. The former is essentially human-centric while the latter is god-centric. To be precise, epics are sublime poetry while Purāṇas are didactical and doctrinal narratives. What film needs as an art is the former, but its commercial outlook always caters to the latter. There is a dire need for a harmonious blend of these aspects, which will take care of aesthetics and sustenance.

The quality of the script in Telugu movies, owing to the high standards of the dialogue writers and lyricists, was far superior to Kannada movies. Movies then were largely theatrical productions that were captured in camera and screened; it is unrealistic to expect a sophisticated grammar of film-making. Cinema was in its infancy, so nothing great could be dreamt of, be it in the realm of aesthetics or technique. It was only the lyrical language that could be exploited in the form of songs and dialogues. Telugu films attracted many great writers from the literary world who were the stalwarts of those times. It never lost touch with its classical theatrical tradition, which was rich in lyrical and poetic values. Hence it was a matter of pride to write for films. This is the reason why it was natural to find flawless classical metres like kandamu, vṛttamu, sīsamu and gītamu along with bombastic dialogues with much inflection and imagery in movies. Great poets like Vishvanatha Satyanarayana, Devulapalli Krishna Sastri, Sri Sri (Srirangam Srinivasa Rao), C. Narayana Reddy, and Arudra (Sadasiva Shankara Sastry) along with the film-world’s own finds like Samudrala, Pingali, Malladi, Veturi, and Sadashiva Brahmam did a great job at infusing profundity to the tinsel world.

It was a different story in Kannada cinema. Kannada also had a rich theatrical tradition, but the classical play structure seasoned by stalwarts like Basavappa Shastri, M. Sitarama Shastri, N. Ananthanarayana Shastri, and M. Ramashesha Shastri was completely ignored. In spite of the presence of able scholars like B. Narahari Shastri, no films in Kannada contain verses composed in chaste metres—kandas and vṛttas—a true measure of classical perfection with regard to language. Luminaries of modern Kannada like Kuvempu, Bendre, PuTiNa and DVG never got along well with the film industry. Perhaps this is because writing for films was looked down upon in Karnataka. Sadly, well-known coastal traditional theatres—Yakṣagāna and Tāla-maddaḻe—were not looked up for inspiration. A wonderful opportunity was lost for no reason.

From the viewpoint of sets, costumes, make-up and filming techniques too, Telugu movie-makers were several notches ahead of their Kannada counterparts. As the epic-mythological films heavily depend on these resources, the Kannada film industry, comparatively modest in economic standards, had to settle for modest means. Many times it had to schedule its shootings during late night, just to save money for the sets by using those which were meant to be used by Telugu/Tamil movies during the day. Even the market for Kannada movies was small. All this naturally resulted in poor productions.

The only saving grace was music. But here again the main singers and most of the music directors were all from Andhra, and were settled in Madras. It was only the talent of some of the great actors and directors along with a set of good scriptwriters and lyricists that made the Kannada epic-mythological films stand out in the annals of Indian film history.

Directors like R. Nagendra Rao, H. L. N. Simha, B. S. Ranga, B. R. Pantulu, Shankar Singh and Hunasur Krishnamurthy, actors like Rajkumar, Udaykumar, Kemparaj Urs, Pandari Bai and B. Saroja Devi, and writers like K. Prabhakara Shastri, C. Sadashivaiah and G. V. Iyer worked hard in this direction. Again, we hardly find exceptional talent meant exclusively for mythological movies. This was not so in the Telugu film world. Directors like K. V. Reddy, K. Kameshwara Rao, and C. Pullaiah and actors like N. T. Rama Rao, Kanta Rao and S. V. Ranga Rao were specially known for their talents in working with movies based on epics.

All this is a saga of the past. Such movies were produced when people from all strata of the society used to enjoy the supernatural and theistic treatment that was being given to the epic themes. But at least later, when the Kannada film industry got the unique distinction of producing ‘art films’ which emphasised realistic and suggestive tones of low-key operation, our movie makers could have ventured into this forgotten direction of epic-mythological themes. For instance, what Shyam Bengal did in some episodes of the tele-serial Bhārat Ek Khoj, or what Aravindan did in his Malayalam movie Kāñcan Sītā could have been done better in Kannada by using, say, an epic novel like Dr. S. L. Bhyrappa’s Parva. Instead of demystifying the epics regardless of reverence and aesthetic sensitivities—which most of the left-leaning writers, movie makers and theatre artists did—our film industry could have ventured into making true epic films that are well-rooted in sublime humanism and rasa of the first order. But this opportunity also went untapped. To this day, such movies have not been attempted, neither in commercial movie circles nor in the realm of art movies. Of course, this remains a sad reality which is applicable to all Indian films irrespective of the language of production. That is why we have not seen an Indian film in the league of Troy, to give a ready example.

The Kannada film industry could not achieve all that it had destined for in the lore of epic-mythological movies. However, we should never ignore the fact that in spite of all limitations, it became successful in reaching out to the masses in propagating our glorious epic and mythological tradition. Going by any estimate, this is really a great service to our country and culture.

This paper was presented at the ‘National Seminar on Kannada Cinema’ held in Bengaluru.

Comments