This unsleeping Inner Eye was also alert to well-intentioned inanities that the fledgling democracy in India was cooking up in rapid succession. One such inanity is our national motto, Satyameva Jayate translated commonly as “Truth alone prevails.” In a brilliantly piercing essay[1] titled India’s Motto, DVG dedicates three pages dissecting this motto down to its last atom. He copiously quotes from the Mundaka Upanishad (where this line occurs), marshals substantial evidence from Sanskrit grammar, traditional Sanskrit commentaries and arrives at significant conclusions regarding the very prudence of selecting this line as our national motto. The essay has to be read in its entirety to savour the rich insights it offers. Using the word “Jayate” transitively will mean “exalting Truth…because it possesses the power to vanquish its opposite…In other words, success or gain is made the criterion of virtue. Is that the best way of honouring Truth? So taken, Satyam-eva-Jayate would merely be another version of the mercantile motto, “Honesty is the best policy.””

Neither does DVG stop at this. He says, “Our concern for Truth should not be utilitarian, but absolute…We adore Satya…not for the sake of the Jaya it may (may not!)… bring, but for its own sake.” And exposes the sheer imprudence of applying this Upanishadic verse in a realm it does not belong: politics and Government. He questions,

“Is that a way that will suit a Government?... As part of its service to Satya, how will the [Government’s] motto “Satyam-eva-jayate” sound in the context of a dishonest public official who has avoided detection and hoarded his ill-gotten money…?... Must a Government have a motto? Must it…exhibit one?... When the Government of India have such questions to decide…they should seek advice not from a close coterie unknown to the public, but from…heads of certain Mutts and a few recognized scholars like Prof P.V. Kane and Prof. M. Hiriyanna.”

A similar but far worse inanity is boldly inscribed on the entrance of the Vidhana Soudha[2] : “Government’s work is God’s work,” which elicited a stern condemnation[3] from a famous litterateur: “Government’s work is a heinous slavery.”

****

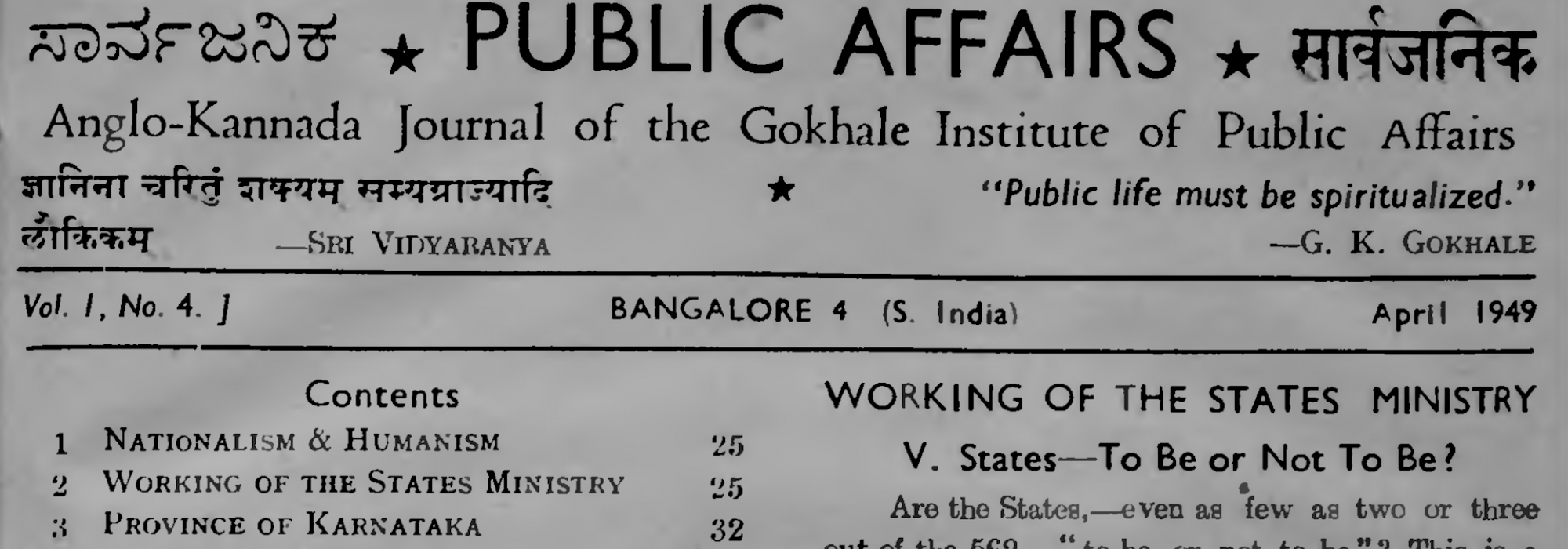

Given the sheer volume of DVG’s splendid critiques of the Congress Party and Governments spread over thirty years, even a condensed rendering will amount to a separate book of a modest proportion. Arguably, these critiques have their roots in two seminal essays he wrote in 1949 in the Public Affairs journal as a series. Both have been mentioned earlier: Congress and Parties and The Congress Ailing. The rest of his Congress-critiques can reasonably be regarded as expansions of and additions to these pioneering essays. Put together, both these essays easily run up to about forty pages.

Indeed, the opening sentence[4] of Congress and Parties is bluntly direct: “The Congress is ailing, both in and out and that is a matter for concern even to those who do not belong to its organization, because the Congress is in charge of the country’s Government all over.”

Seven decades after it was written, Congress and Parties remains an invaluable classic in its genre, ever-relevant. It is also a great study in how to write political analyses that are original, objective, comprehensive, truthful, and ethical. The central themes of Congress and Parties hinge on the following:

· How the Congress descended to political promiscuity immediately after India attained political independence.

· How it systematically stifled internal democracy under the excuse of party discipline and how the nation had to pay a huge price for it.

· The emergence of the High Command culture, which under the garb of maintaining intra-party harmony stifled internal debate, dissent and free expression.

· The absolute urgency of birthing rival political formations to the Congress in order to safeguard Indian democracy.

DVG correctly endorses Mohandas Gandhi’s recommendation that the Congress should shut down its political activity after Independence and dedicate itself to the task of nation-building. With great foresight, DVG notes[5] that if Gandhi’s advice had been accepted, “political parties would have…formed afresh, independently of the Congress, and that would have been an advantage to the country.”

As we have noted numerous times in this book, DVG’s analyses considered that vital component missing in typical and superficial political writings: human nature. This keen understanding is precisely what gives us[6] such gems:

Power is as much a disintegrator as it is an integrator. So long as power remained a far-off object to be fought for…the rank and file in the Congress…[were united]. It is just as natural that after the prize has been captured, there should be a scramble among them for shares. Search unites. Gain divides. This is the law of human nature.

Thus, from being a patriotic and nationalist organization whose objective was getting rid of British rule, the Congress crashed down to becoming a purely political outfit immediately after freedom thereby immediately debasing its stature. DVG notes that its tearing power-hunger led to rampant political promiscuity, some facets of which we have seen in an earlier section. This is how DVG characterizes the hasty and staggering downfall of the Congress:

Great undoubtedly is the Congress; but the country is greater. Congress [was] great because it till now recognized the country as greater.

Equally, the sheer stature, pan-Indian spread and dominance of the Congress ensured that even the thought of an alternative political formation did not arise due to the sheer terror it inspired. DVG describes[7] this as the Congress “outgrowth,” which shut down all “open-minded study” and how there were no public meetings in the country “other than those organized by the Congress.” And more acidly, “Like the Upastree (concubine), the Congress will let no other organism thrive anywhere in its neighbourhood.” This sort of quasi-dictatorship also manifested itself in other ways. The most notable ignoble precedent[8] is the infamous Romesh Thapar vs The State Of Madras case. Romesh Thapar, part of Jawaharlal Nehru’s circle had upset the Prime Minister by daring to criticize him in his paper. Nehru’s Government sued him and lost the case. Unwilling to accept this loss of face, Nehru used the full might of his power and influence to bulldoze the first amendment to Article 19 of the Constitution which guarantees freedom of speech and curbed it using the vague terminology of “free speech subject to reasonable restrictions.”

Thus, with virtually no opposition either in Parliament or legislatures, the Congress turned upon itself in a Shakespearian sense. The first casualty was a systematic stifling of intra-party democracy under the garb of party discipline. DVG observes how even someone like Acharya Kriplani (a former Congress President) was humiliated under this excuse and was made to issue a cringeworthy apology[9] in public for daring to speak the unpleasant truth even in the “freedom of friendly conversation.” The Congress Party now demanded and got “submission and acquiescence miscalled harmony.” In reality, the Congress was implementing a milder version of the forced, public confessions of guilt by the members of the Communist Party of Russia in those innumerable notorious show trials of Stalin. DVG correctly traces this corrupt phenomenon as the first stirrings of the dictatorship of the Congress High Command, which assumed fearsome proportions over time.

Simultaneously, DVG points out that one swallow makes not a summer when that other familiar excuse is forwarded: that we have great leaders at the Centre and at the top party leadership and the party and country is largely in safe hands. He counters[10]: “The point…is not what giants we have at the Centre, but what dwarfs we have at so many other key-points.”

To be continued

Notes

[1] D.V. Gundappa: India’s Motto, Public Affairs, June 1949, Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs, Bangalore pp 47 – 49

[2] The building which houses the Karnataka Legislature

[3] A.N. Krishna Rao, the renowned Kannada novelist, writer, and activist.

[4] D.V. Gundappa: Congress and Parties, Public Affairs, April 1949, Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs, Bangalore p 33. Emphasis added.

[5] Ibid. Emphasis added.

[6] Ibid. Emphasis added.

[7] D.V. Gundappa: Congress and Parties, Public Affairs, May 1949, Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs, Bangalore p 42. Emphasis added.

[8] For the full text of the judgment, see: https://indiankanoon.org/doc/456839/

[9] D.V. Gundappa: Congress and Parties, Public Affairs, May 1949, Gokhale Institute of Public Affairs, Bangalore p 42.

[10] Ibid p 40. Emphasis added.