It is hard to determine the period and place in which Bhaṭṭa-nārāyaṇa, the author of Veṇī-sāṃhāra lived. Vāmana (4, 3-28), and other aestheticians quote examples from his play. Vāmana lived in about 800 CE; therefore, it is safe to say that Bhaṭṭa-nārāyaṇa lived before this period.

From the prastāvana of the play, we learn that Bhaṭṭa-nārāyaṇa was also known as Mṛgarāja; it was probably a prefix to his name. The word mṛgarāja means a lion – a siṃha; thus, some scholars think that Siṃha must have been Bhaṭṭa-nārāyaṇa’s prefix or a secondary name. It looks unlikely that a person would prefer to have the word mṛgarāja as a part of his name, instead of the more popular and easy-to-pronounce word siṃha.

We learn that Bhaṭṭa-nārāyaṇa was a brāhmaṇa; King Ādi-śūra is supposed to have invited him to Bengal from Kānjyakubja. From this, scholars such as Sten Konow estimate that Bhaṭṭa-nārāyaṇa must have lived in the second half of the seventh century CE. However, this cannot be established with certainty.

His Veṇī-sāṃhāra has been appreciated by aestheticians and scholars for centuries. It is a play in six acts. The summary of the plot is as follows –

Śrī-kṛṣṇa is in the Kaurava court to barter peace; Bhīma, however, is impatient. In the meantime, Draupadī informs Bhīma the manner in which Bhānumatī ridiculed her – this further amplifies Bhīma’s anger. The Pāṇḍavas hear that attempts at a treaty of peace have been unsuccessful. (Act 1).

Bhānumatī has a nightmare; to undo the bitter consequences of her dream, she observes certain rituals, but Duryodhana comes in the way of her vow. He sees bad omens – the banner on his chariot breaks apart due to heavy wind; Jayadratha’s mother and wife rush to Duryodhana to inform him of Arjuna’s pledge; he consoles them and sends them back (Act 2).

(Saindhava and Ghatoṭkaca die – praveśaka) Aśvatthāmā, who is angry with the Pāṇḍavas upon learning the manner in which his father, Droṇācārya, breathed his last, comes to Duryodhana and asks to be elevated to the position of commander-in-chief. However, Duryodhana tells him that he had already decided to make Karṇa the commander-in-chief. In the meantime, Karṇa, who was nearby, is distraught because of the humiliating words he has heard; he gets into a verbal fight with Aśvatthāmā, who pledges that he won’t engage in a fight until Karṇa falls. He gives up his weapons and goes away (Duśśāsana is killed). Description of the battle between Karṇa and Arjuna (Act 4).

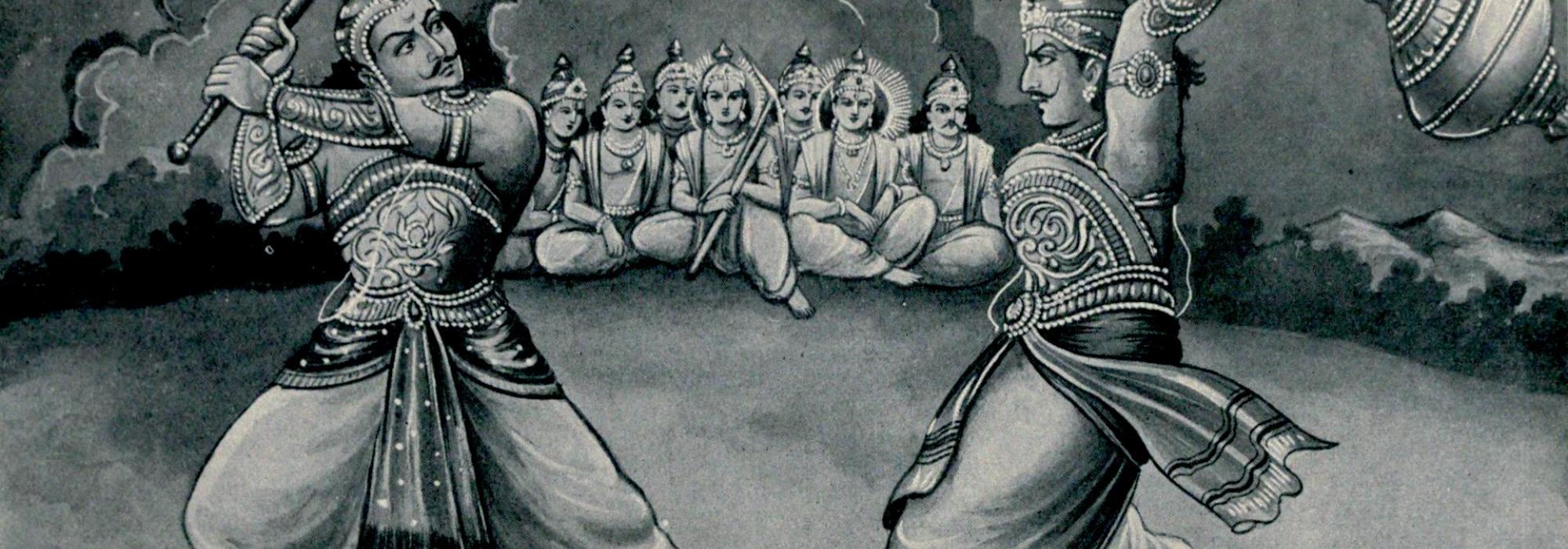

Dhṛtarāṣṭra and Gāndhārī see Duryodhana on the battlefield and advise him to enter a treaty of peace; the news of Karṇa’s defeat reaches them; Duryodhana puts aside Aśvatthāmā ’s repeated requests and assumes the post of the commander-in-chief himself; he is enraged and determined to kill his enemies. Bhīma and Arjuna arrive there. A verbal duel ensues between Bhīma and Duryodhana; Bhīma pledges that he will kill Duryodhana before the following evening (Act 5).

Duryodhana, who was hiding in a lake, is found; the news that a combat between him and Duryodhana is going to take place reaches Dharmarāja and Draupadī. In the meantime, Cārvāka, Duryodhana’s friend, comes in the disguise of a ṛṣi there; he reports that Bhīma is dead, and it is likely that Arjuna is slain as well. Upon hearing this, Dharmarāja and Draupadī get ready to enter the fire. Bhīma kills Duryodhana and comes to their abode looking for Draupadī, his body soaked with blood; everyone mistakes him for Duryodhana and is scared. Finally, they understand the reality and ‘veṇī-sāṃhāra’, i.e., braiding of the long tresses of Draupadī, happens. Krishna and Arjuna arrive there as well; they tell the others about the Chaarvaka and also that he was slain by Nakula. Dharmarāja is coronated (Act 6).

The Veṇī-sāṃhāra is, thus, a play that encompasses the story starting from Kṛṣṇa-sandhāna to Duryodhana-saṃhāra. The poet has displayed great skill in condensing this long story into a play –he has ensured that the story is engaging and that the characters are presented well. His creative talent, we may say, is on par with that of Bhāsa and Viśākhadatta in this sense – they have the skill of narrating a long tale in the form of a play. Though Bhaṭṭa-nārāyaṇa is similar to them in many cases, he is slightly inferior in certain ways. Moreover, he is a product of his times – in the times contemporary to him, certain principles of aesthetics have affected the structure and content of his play – the understanding of literature and perspective towards life was slightly different in his times than that which existed during the times of the earlier playwrights. These elements must have contributed to bringing down the quality of the play. Veṇī-sāṃhāra stands as an example of a naturally gifted poet delivering a rather mediocre product under the influence of his times.

To be continued ...

The current series of articles is an enlarged adaption of Prof. A. R. Krishnasastri's Kannada treatise Saṃskṛta-nāṭaka. They are presented along with additional information and footnotes by Arjun Bharadwaj.