After introducing the major characters, Śūdraka has gone on to describe the nucleus of his story in all its complex shades. Keeping this in mind, let us try to understand the extent of scope that a social play offers to various rasas. According to Indian dramaturgy, a prakaraṇa involving commonfolk is not the best type of play to delineate the heroic mood, vīra-...

Aśvaghoṣa clearly states that his work is principally a scripture. It is structured as a poem, yes, but that is only a veneer, a convenient pretence. Nevertheless, his work is appealing because of two reasons: one, he was a gifted poet; two, he chose the lofty story of the Buddha’s life as his subject. From this we understand that at times even purpose-driven compositions get the glitter of pure poetry. We should be wary of the fact that not all...

Modern literary theory usually insists that a poet should not come in the way of the natural development of events and characters. If he gets personally involved, the work runs the risk of turning into a pamphlet meant only to air the author’s pet views. It would then become an artificial construct, straying away from its primary purpose of leading the readers to rasa.

...

At the outset of the Mahābhārata Vyāsa outlines its literary qualities that befit an epic. At the end of the epic, he composes an epilogue of sorts titled Bhāratasāvitrī, where he solemnly records the poet’s helplessness:

ऊर्ध्वबाहुर्विरौम्येष न च कश्चिच्छृणोति मे।

धर्मादर्थश्च कामश्च स किमर्थं न सेव्यते॥ (१८.५.४९)

I scream with raised arms: Dharma is the...

In the next verse Vyāsa describes a defining trait of great poets. He intends this as a lodestar of sorts of his work:

इतिहासप्रदीपेन मोहावरणघातिना।

लोकगर्भगृहं कृत्स्नं यथावत् संप्रकाशितम्॥ (१.९६.१०३, Kumbhakonam edition)

The great lamp of itihāsa dispels darkness in the form of stupor, ignorance, delusion. It illuminates the inner core of the world and shows it as it is.

Itihāsa is a word that is pregnant with meaning....

In these verses Vyāsa has succinctly described the central focus of his poem and the nature of its characters. This is the way of great poets: they present the essence of the story upfront and then go on to narrate how it evolves. Lesser poets present the story in bits and pieces, intending to keep the readers hooked till the end. They sometimes stretch this technique to extreme limits, thus stripping the story of suggestive value and rendering...

Rāma savoured the recital amid a large group of literary aficionados: sa cāpi rāmaḥ pariṣadgataḥ (1.4.36). This is arguably the best way to appreciate art because people with a refined aesthetic sense assist one another in discovering newer and newer subtleties, thus raising the level of overall enjoyment.

Uttarakāṇḍa has many...

Vālmīki was absorbed in thoughts about his verse when Brahmā visited him: tadgatenaiva manasā vālmīkirdhyānamāsthitaḥ (1.2.28). He was tormented by the impropriety in hunting the male bird and the consequent anguish caused to its companion. Here is a poet mulling over the incident that inspires his poetry. If worldly events do not evoke such a profound response in a writer, they cannot inspire poetry. In its highest reaches, poetry is the...

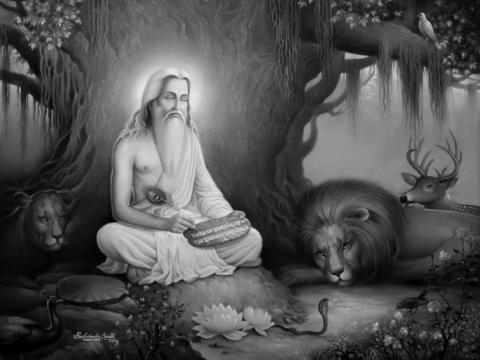

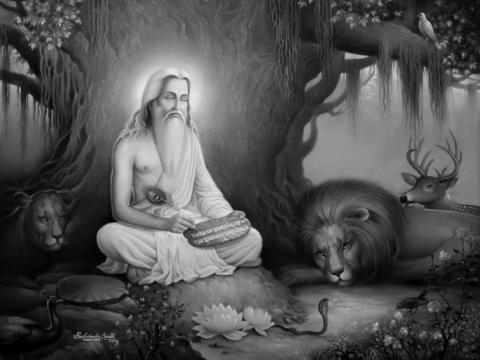

Maharṣi Vālmīki

The story narrated in the first four cantos of the Rāmāyaṇa is of great significance to the central concepts of the creative process: poet, poetry and connoisseur. In the opening canto, Ādikavi Vālmīki questions Maharṣi Nārada about the ideal human being, the model protagonist. This simple enquiry has far-reaching undertones. It has supplied flavour to the dry and rather unintelligible aesthetic dictum that expects the hero of a...

Art appreciation begins with learned connoisseurs. Gaining breadth and vision with time, it develops into a well-structured system of aesthetics. Poets and artists often find it hard to explain the aspects of appeal inherent in the form and substance of their compositions. They have neither the bent of mind nor the competence to subject their work’s appeal to a logical analysis. Only a handful of artists can tell us what goes into the making of...

- « first

- ‹ previous

- 1

- 2

- 3